- Full track break-down using the principles taught in the Science of Speed Series.

- A self-guided, low-cost alternative or supplement to our track coaching services.

- Bonus "Corner Close-Up" on the reverse for extra in-depth analysis of the most difficult and complex section.

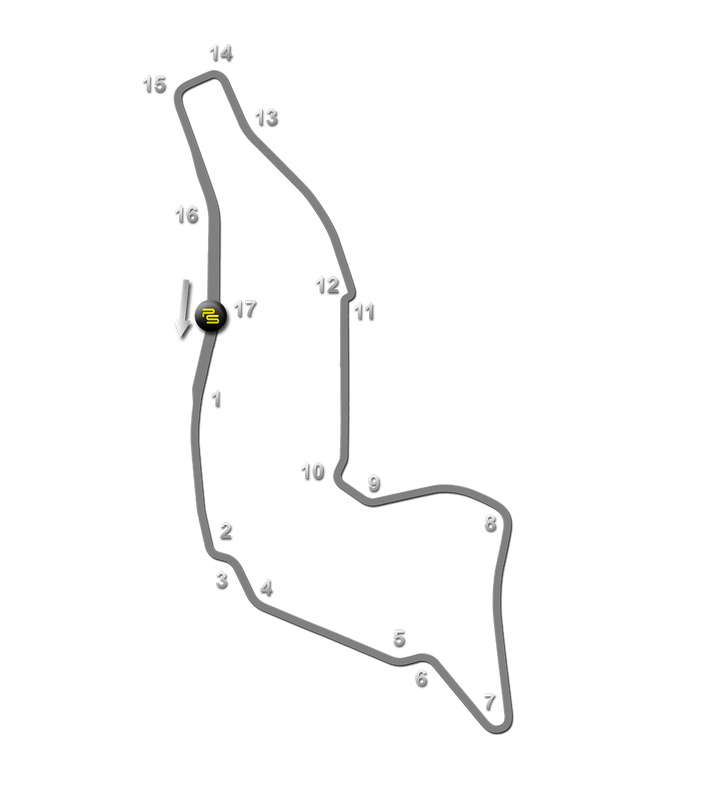

Imola Track Guide Map

Circuit History

Imola will forever be tainted by the tragedies of 1994 which prompted major revisions to its layout but, despite this, it remains one of the most atmospheric and challenging circuits in Europe.

The circuit is in an area with long associations with speed – as far back as 80BC the Romans created an amphitheater for gladiatorial chariot racing. In more recent times, the idea for a motor racing circuit was first promoted in the late 1940s. Four locals – Alfredo Campagnoli, Graziano Golinelli, Ugo Montevecchi and Gualtiero Vighi – who were all keen on motorcycle racing, saw the opportunity presented by the creation of a new road. This linked the via Emila, where the Rivazza curve is now located, to the town of Codrigano, as far as the current Tosa curve.

Winning support for an autodrome under the guise of using the construction to help relieve unemployment, a series of connecting roads were created to form an anti-clockwise loop. The first foundation stone was laid in March 1950, with Enzo Ferrari himself present. It was not until October 1952 that the first testing could take place, with Ferrari dispatching a 340 Sport for Ascari, Marzotto and Villoresi to try out, lapping at an average of 149 km/h. Also present were the Gilera and Moto Guzzi motorcycle teams, with riders able to achieve an average speed of 138 km/h.

The original circuit layout travelled the familiar route alongside the river to Tosa, up the hillside to Piratella and Acque Minerale, before plunging back down towards the Rivazza. While the track layout itself is largely unchanged, little else would be recognizable to racegoers today – essentially, the circuit resembled the largely temporary facility it was, a simple connection of the roads and streets of a city suburb, replete with all of the hazards this brings.

Initially named after the Santerno River which borders it on the paddock side, the circuit was renamed Autodromo Dino Ferrari in 1970 after Enzo Ferrari's son, who had died of leukemia in 1956. Enzo Ferrari's own name was added following his death in 1988.

The first racing events were held in April 1953, with the GP Coni motorcycle race which was approved for the 125cc and 500cc Italian championship. The following year the first car races arrived in the form of the Coppa d'Oro Shell ('Golden Shell' race), which was open only to sports cars and would see Ferrari and Maserati compete for victory, the Ferrari of Magioli eventually proving victorious. In the same year, the circuit's management was entrusted to E.S.T.I. (Imola's Sport and Tourism Body), with Tommaso Maffei Alberti as President.

Those early years saw Imola establish itself mainly as a sports car and motorcycle venue, but in 1963 it organized its first international race run to Formula One rules. Jim Clark proved a runaway winner in a Lotus 25, though organizers were disappointed that there was no entry for Ferrari. Similarly, the first World Championship Motorcycle event took place in 1969 without the most prestigious home manufacturer, as MV Augusta was not present.

Gradual improvements were made to the facilities; in 1965, the first covered grandstand was erected on the start/finish straight, while some sections were resurfaced and widened, including at Tosa, were new run off areas and spectator banking was provided in 1970, along with sections of Armco barrier at key points.

The first major layout revision came in August 1972, with the construction of the Variente Bassa (lower) chicane, and from 1974 the Variente Alta (higher) chicane was also added to slow speeds on the approach to Rivazza.

Into the mid 1970s, Imola was still a collection of public and private roads, but the decision was taken at the end of the decade to formalize affairs and create a true permanent facility for the first time. Roads were closed off to public traffic and construction work around the circuit saw it emerge with barriers all round, grandstands and new pit buildings.

The reward was a Formula One Grand Prix – initially a non-championship affair in 1979, won by the Brabham of Niki Lauda – and then in 1980, the Italian Grand Prix was awarded to Imola following a dispute with organizers at the Monza circuit. From 1981, Imola was granted a race alongside Monza under the guise of the nearby Republic of San Marino, an event it would host for the next quarter century.

Further circuit changes were made for the 1981 season, based on feedback from the first two F1 events. A lack of run-off at Acque Minerale was solved by the insertion of a somewhat clumsy chicane. At Variente Alta, meanwhile, for the return of the Motorcycling World Championship, a temporary second chicane was added for use during bike events only. A further chicane at Villeneuve corner was added in 1985, again only for use by motorcycle racers, though the world championship racers got only one opportunity to sample it in 1988 before the race switched permanently to nearby Misano.

Despite the addition of the various chicanes, the circuit was subject to constant safety concerns, mostly regarding the flat-out Tamburello corner, which was very bumpy and had dangerously little room between the track and a concrete wall which protects the river behind it. In 1987, Nelson Piquet was injured after crashing there in his Williams, missing the race as a result. Worse was to come in 1989, when Gerhard Berger's Ferrari left the circuit after a front wing failure and caught fire. Rapid work by marshals ensured the flames were quickly extinguished but Berger had suffered burns to his hands, which would see him miss the following Grand Prix.

Then came Formula One's blackest weekend. During Friday practice for the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, Rubens Barrichello was lucky to emerge with relatively light injuries when he crashed his Jordan-Hart at the Variente Bassa, launching over the curbing into the debris fencing. The following day, Roland Ratzenberger was killed when he crashed at Villeneuve and in the race itself, spectators were injured when debris from a startline collision went into the crowd. Then, Formula One's biggest star Ayrton Senna suffered fatal injuries when his car left the track at Tamburello, and mechanics were injured in the restarted race when a wheel came loose from a Minardi.

The events in Imola rocked the motor racing world and forced immediate changes in car and circuit design. Imola itself underwent a total reconstruction in the winter of 1994, emerging in much modified form. Tamburello was no more, replaced by a chicane, as was the case at Villeneuve. Run off was much improved around the circuit, including at Rivazza, which had been repositioned and the corners made tighter. Acque Minerale was, however, restored as proper corner, albeit with greatly increased run-off.

Formula One events would continue successfully for another decade and, between 1996 and 1999, the MotoGP also returned, meaning that for a brief period Imola was one more home to the top classes in two and four wheels. However, MotoGP departed in 2000, to be replaced a year later by the World Superbike Championships. Storm clouds were gathering by this time, with discontent in the Formula One about the state of the pit and paddock facilities — which were essentially unchanged from the 1979 rebuild — and a general impetus for new races in the Far East. The inevitable happened in August 2006, when the FIA dropped the San Marino Grand Prix from the F1 calendar, unless improvements could be made to the circuit.

Against this background, track operator SAGIS ploughed ahead with plans to modernize, employing Herman Tilke to design new pit and paddock facilities. These call for a lengthened pit lane, which would result in the removal of the Variante Bassa chicane altogether. In November 2006, the existing pit buildings (save for the iconic Marlboro Tower) were demolished, in preparation for revisions. It was to prove the last act of SAGIS, which filed for bankruptcy in early 2007, bringing work on site to an abrupt halt. The Municipality of Imola launched a tender for the thirty-year management of the circuit, awarding it in February 2007 to a new company, 'Formula Imola', which is a joint venture between the city and the Norman property group. Work resumed on the reconfiguration, but the delays mean that no racing could be held during 2007.

The revised circuit was inaugurated in May 2008, hosting a round of the World Touring Car Championship for the first time in August. At the end of the year, the Norman property group bowed out of ownership and the majority stake in Formula Imola was bought by the Motorsport Eventi company. A push for more international events saw the return of the World Superbikes in 2009, though a new Variente Bassa chicane was added just ahead of the start/finish line at the request of the FIM. This is only utilized by the motorcycle racers.

The debts accrued by the circuit modernization sent Formula Imola into administration again in February 2010, though the circuit continued to operate on a provisional basis while new ownership was sought. Under the administrator, the circuit's debts were addressed, such that by October 2010 it was removed from administration once more. A reorganization to form a new holding company, Con-Ami, took place in December of that year. Con-Ami was subsequently awarded the rights to run the circuit for 64 years in 2012.

The revived circuit has gone on to consolidate its position, continuing to host the World Superbike Championships but also reviving top class sportscars with the Six Hours of Imola, run to Le Mans rules as part of the Intercontinental Le Mans Cup in 2011. Subsequently, a shortened three-hour race has formed a round of the European Le Mans Series. A complete resurface was undertaken in August 2011, after which the FIA awarded the circuit Grade 1 status once again, licensing it for Formula One competition; while a revival of the San Marino Grand Prix is unlikely the current financial climate, the certification does mean that the venue is at least able to host F1 testing once again.

Imola will forever be tainted by the tragedies of 1994 which prompted major revisions to its layout but, despite this, it remains one of the most atmospheric and challenging circuits in Europe.

The circuit is in an area with long associations with speed – as far back as 80BC the Romans created an amphitheater for gladiatorial chariot racing. In more recent times, the idea for a motor racing circuit was first promoted in the late 1940s. Four locals – Alfredo Campagnoli, Graziano Golinelli, Ugo Montevecchi and Gualtiero Vighi – who were all keen on motorcycle racing, saw the opportunity presented by the creation of a new road. This linked the via Emila, where the Rivazza curve is now located, to the town of Codrigano, as far as the current Tosa curve.

Winning support for an autodrome under the guise of using the construction to help relieve unemployment, a series of connecting roads were created to form an anti-clockwise loop. The first foundation stone was laid in March 1950, with Enzo Ferrari himself present. It was not until October 1952 that the first testing could take place, with Ferrari dispatching a 340 Sport for Ascari, Marzotto and Villoresi to try out, lapping at an average of 149 km/h. Also present were the Gilera and Moto Guzzi motorcycle teams, with riders able to achieve an average speed of 138 km/h.

The original circuit layout travelled the familiar route alongside the river to Tosa, up the hillside to Piratella and Acque Minerale, before plunging back down towards the Rivazza. While the track layout itself is largely unchanged, little else would be recognizable to racegoers today – essentially, the circuit resembled the largely temporary facility it was, a simple connection of the roads and streets of a city suburb, replete with all of the hazards this brings.

Initially named after the Santerno River which borders it on the paddock side, the circuit was renamed Autodromo Dino Ferrari in 1970 after Enzo Ferrari's son, who had died of leukemia in 1956. Enzo Ferrari's own name was added following his death in 1988.

The first racing events were held in April 1953, with the GP Coni motorcycle race which was approved for the 125cc and 500cc Italian championship. The following year the first car races arrived in the form of the Coppa d'Oro Shell ('Golden Shell' race), which was open only to sports cars and would see Ferrari and Maserati compete for victory, the Ferrari of Magioli eventually proving victorious. In the same year, the circuit's management was entrusted to E.S.T.I. (Imola's Sport and Tourism Body), with Tommaso Maffei Alberti as President.

Those early years saw Imola establish itself mainly as a sports car and motorcycle venue, but in 1963 it organized its first international race run to Formula One rules. Jim Clark proved a runaway winner in a Lotus 25, though organizers were disappointed that there was no entry for Ferrari. Similarly, the first World Championship Motorcycle event took place in 1969 without the most prestigious home manufacturer, as MV Augusta was not present.

Gradual improvements were made to the facilities; in 1965, the first covered grandstand was erected on the start/finish straight, while some sections were resurfaced and widened, including at Tosa, were new run off areas and spectator banking was provided in 1970, along with sections of Armco barrier at key points.

The first major layout revision came in August 1972, with the construction of the Variente Bassa (lower) chicane, and from 1974 the Variente Alta (higher) chicane was also added to slow speeds on the approach to Rivazza.

Into the mid 1970s, Imola was still a collection of public and private roads, but the decision was taken at the end of the decade to formalize affairs and create a true permanent facility for the first time. Roads were closed off to public traffic and construction work around the circuit saw it emerge with barriers all round, grandstands and new pit buildings.

The reward was a Formula One Grand Prix – initially a non-championship affair in 1979, won by the Brabham of Niki Lauda – and then in 1980, the Italian Grand Prix was awarded to Imola following a dispute with organizers at the Monza circuit. From 1981, Imola was granted a race alongside Monza under the guise of the nearby Republic of San Marino, an event it would host for the next quarter century.

Further circuit changes were made for the 1981 season, based on feedback from the first two F1 events. A lack of run-off at Acque Minerale was solved by the insertion of a somewhat clumsy chicane. At Variente Alta, meanwhile, for the return of the Motorcycling World Championship, a temporary second chicane was added for use during bike events only. A further chicane at Villeneuve corner was added in 1985, again only for use by motorcycle racers, though the world championship racers got only one opportunity to sample it in 1988 before the race switched permanently to nearby Misano.

Despite the addition of the various chicanes, the circuit was subject to constant safety concerns, mostly regarding the flat-out Tamburello corner, which was very bumpy and had dangerously little room between the track and a concrete wall which protects the river behind it. In 1987, Nelson Piquet was injured after crashing there in his Williams, missing the race as a result. Worse was to come in 1989, when Gerhard Berger's Ferrari left the circuit after a front wing failure and caught fire. Rapid work by marshals ensured the flames were quickly extinguished but Berger had suffered burns to his hands, which would see him miss the following Grand Prix.

Then came Formula One's blackest weekend. During Friday practice for the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, Rubens Barrichello was lucky to emerge with relatively light injuries when he crashed his Jordan-Hart at the Variente Bassa, launching over the curbing into the debris fencing. The following day, Roland Ratzenberger was killed when he crashed at Villeneuve and in the race itself, spectators were injured when debris from a startline collision went into the crowd. Then, Formula One's biggest star Ayrton Senna suffered fatal injuries when his car left the track at Tamburello, and mechanics were injured in the restarted race when a wheel came loose from a Minardi.

The events in Imola rocked the motor racing world and forced immediate changes in car and circuit design. Imola itself underwent a total reconstruction in the winter of 1994, emerging in much modified form. Tamburello was no more, replaced by a chicane, as was the case at Villeneuve. Run off was much improved around the circuit, including at Rivazza, which had been repositioned and the corners made tighter. Acque Minerale was, however, restored as proper corner, albeit with greatly increased run-off.

Formula One events would continue successfully for another decade and, between 1996 and 1999, the MotoGP also returned, meaning that for a brief period Imola was one more home to the top classes in two and four wheels. However, MotoGP departed in 2000, to be replaced a year later by the World Superbike Championships. Storm clouds were gathering by this time, with discontent in the Formula One about the state of the pit and paddock facilities — which were essentially unchanged from the 1979 rebuild — and a general impetus for new races in the Far East. The inevitable happened in August 2006, when the FIA dropped the San Marino Grand Prix from the F1 calendar, unless improvements could be made to the circuit.

Against this background, track operator SAGIS ploughed ahead with plans to modernize, employing Herman Tilke to design new pit and paddock facilities. These call for a lengthened pit lane, which would result in the removal of the Variante Bassa chicane altogether. In November 2006, the existing pit buildings (save for the iconic Marlboro Tower) were demolished, in preparation for revisions. It was to prove the last act of SAGIS, which filed for bankruptcy in early 2007, bringing work on site to an abrupt halt. The Municipality of Imola launched a tender for the thirty-year management of the circuit, awarding it in February 2007 to a new company, 'Formula Imola', which is a joint venture between the city and the Norman property group. Work resumed on the reconfiguration, but the delays mean that no racing could be held during 2007.

The revised circuit was inaugurated in May 2008, hosting a round of the World Touring Car Championship for the first time in August. At the end of the year, the Norman property group bowed out of ownership and the majority stake in Formula Imola was bought by the Motorsport Eventi company. A push for more international events saw the return of the World Superbikes in 2009, though a new Variente Bassa chicane was added just ahead of the start/finish line at the request of the FIM. This is only utilized by the motorcycle racers.

The debts accrued by the circuit modernization sent Formula Imola into administration again in February 2010, though the circuit continued to operate on a provisional basis while new ownership was sought. Under the administrator, the circuit's debts were addressed, such that by October 2010 it was removed from administration once more. A reorganization to form a new holding company, Con-Ami, took place in December of that year. Con-Ami was subsequently awarded the rights to run the circuit for 64 years in 2012.

The revived circuit has gone on to consolidate its position, continuing to host the World Superbike Championships but also reviving top class sportscars with the Six Hours of Imola, run to Le Mans rules as part of the Intercontinental Le Mans Cup in 2011. Subsequently, a shortened three-hour race has formed a round of the European Le Mans Series. A complete resurface was undertaken in August 2011, after which the FIA awarded the circuit Grade 1 status once again, licensing it for Formula One competition; while a revival of the San Marino Grand Prix is unlikely the current financial climate, the certification does mean that the venue is at least able to host F1 testing once again.