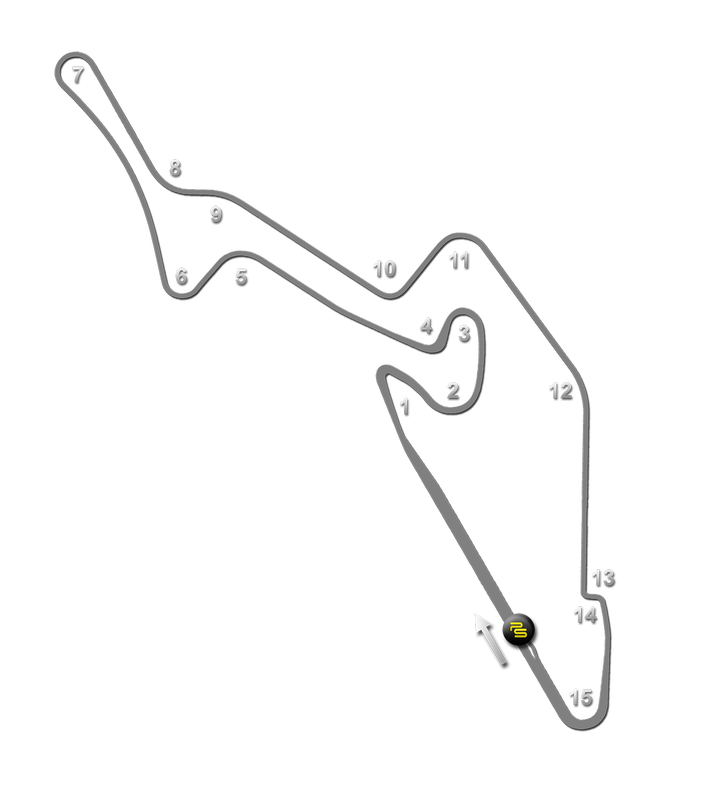

- Full track break-down using the principles taught in the Science of Speed Series.

- A self-guided, low-cost alternative or supplement to our track coaching services.

- Bonus "Corner Close-Up" on the reverse for extra in-depth analysis of the most difficult and complex section.

Nürburgring GP course Guide

Circuit History

Above all other circuits, the Nürburgring has a history and tradition which is intertwined with that of the motorsport itself. The 'Green Hell', as Jackie Stewart so memorably described it, has been thrilling and terrifying drivers in equal measure since 1927 and any event here remains one of the greatest spectacles and challenges on the sporting calendar.

Like many of the lavish venues established in the modern era by oil-rich states seeking to boost their country's international status, the Nürburgring owes its existence to political manoeuvrings. When in 1907, Felice Nazzaro won the Kasierpreis for the Italian Fiat outfit at Taunus, near Frankfurt, German pride took a severe dent. When the Kaiser demanded an explanation for the unexpected result, he was told that the defeat was due to the German manufacturers having no suitable home track to develop and race their vehicles.

Imperial consent was soon given to create such a facility and plans began to be formulated for a world-beating track in the region surrounding the town of Adenau near the Eifel Mountains. But just as the project gathered steam in earnest, World War I intervened and trivial pursuits such as racing took a back seat.

Emerging defeated from the war, Germany was a broken nation, with a valueless currency, mass unemployment and hardship in almost every family. Yet it was just this backdrop which saw the plans for the circuit revived. While tentative moves in 1920 foundered due to a lack of funds, supporters of the project persevered, convinced it could offer a competitive advantage for the resurgent German motor industry.

One man in particular stands as the father of the Nürburgring; Dr Otto Creutz was chair of the ADAC (Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobile Club) and a passionate believer in the project. He reached agreement with the Mayor of Cologne (and future Chancellor) Konrad Adenauer for the project to go ahead as a means of relieving the chronic unemployment in the region.

The first stone was laid on September 27, 1925, and for the next two years around 2,500 workmen laboured to construct the circuit. The basic layout was set by Hans Weidenbrück, using the rolling hillsides and plateaus around the Schloß Nürburg to create a massive circuit that was a true test of both man and machine. Designed to be completely separate from the public road network, it nevertheless incorporated a certain amount of normal road character, increasing its relevance for automobile testing. In part, existing roads and trails were followed, particularly in the area from Hatzenbach to Adenauer Forst and much of the Südschleife, while other sections were totally new, particulalry from Breidscheid to Hedwigshöhe.

There were two main circuits, a northern loop (Nordschleife in the local language) of 14.18 miles and a shorter southern circuit, the Südschleife at 4.81 miles long. Where the two intersected at the shared start/finish straight, a short link circuit could also be used, popularly known as the Betonschleife ('Concrete Loop') though officially titled Start-und-Ziel-Schleife. Both north and south loops could be combined to form 17.58 mile leviathon, though this was rarely used for racing beyond the 1931 season. In addition, a steep test track, the Steilstrecke, was also constructed to make use of the steep climb between Klostertal and Hohe Acht and featuring gradients of up to 27%.

The new circuit was constructed in four sections, each by a different contractor, with the Nordschleife completed first in 1926, the Südschleife and Steilstrecke courses being completed the following year. Innovations at the new course included a large garaged paddock area, connected to the pits via a tunnel, a 10,000 seat grandstand (another quickly followed), a hotel, restaurant and control tower. A series of telephone connections allowed for communication around the giant northern loop by post-to-post calls at 10 (later 16) marshal huts.

Total costs for construction ran to 15 million marks, including 6 million marks provided by the government and substantial finance from the city of Cologne. A competition was held to name the new circuit, with the winning entry suggested by a retired government official from Bad Godesberg.

The Nordschleife opened for racing action in June 1927, with the first race actually for motorbikes on June 18 and won by Tony Ulmen on a Velocette. The following day Rudolph Caracciola entered the record books as the first four wheeled winner, triumphing in a supercharged Mercedes S. The Grand Prix arrived on July 17, won in another Mercedes S by Otto Merz. Thereafter the 'Ring established itself as one of the toughest Grands Prix on the racing calendar.

One of the Nordschleife's defining characteristics found itself literally set in stone (well, concrete) during the 1933 season. At the Karrousel, Rudolf Carraciola had been in the practice of hooking his inside wheel into the ditch to guide the car round – gaining himself as much as two seconds per lap in the process. After several years where other competitors began to copy this innovation, the ditch was finally concreted over and the banked corner was born. Over time, the banked section was extended further, allowing the whole car to be positioned on the concrete section allowing for a slingshot around the hairpin.

World War II provided an inevitable interruption to activities. The Sporthotel grandstand was set up to accommodate evacuees from bombed cities and later served as a military hospital. Other parts fo the circuit were turned into arable and pasture land – cattle even being kept in the lower rooms of the Mercedes tower. In the last months of the war the track was badly damaged by the tanks of the advancing Allies and the grandstand hotel and administrative buildings were destroyed.

When peace returned, the process of rebuilding and reopening the circuit began. The Südschleife reopened first, hosting a motorcycle Eifel Cup race in August 1947. To attract the crowds, race organizers took the novel approach of offering every ticket holder a meal of two sausages, potato salad, bread and half a liter of wine. Unsurprisingly, it worked and people flocked to the meeting.

A year later and the repair works began on the Nordschleife, with racing resuming in May 1949. Soon racing categories of all kinds returned, from sportscars to single seaters. Formula Two came first in 1950, followed by Formula One in 1951. The Nürburgring was back as an international venue of note.

The Dunlop scoring tower was erected in 1954, the first electronic scoring board of its type in the world. Various resurfacings took place in the following years; the start/finish in 1957, Schwedenkreutz to Pflantzgarten in 1965. Still the circuit retained its narrow hedge and tree-lined corners and safety concerns grew. Over the years, several drivers lost their lives; Čeněk Junek is generally regarded as the first in 1928, but Onofre Marimón, Peter Collins, Count Carel Godin de Beaufort and Gerhard Mitter also all perished while racing on the Nordschliefe.

By the end of the 1960s, the first significant changes began to be made in response to these mounting safety concerns. After several near-misses with the Dunlop scoring tower as cars drifted through the high-speed curve that lead from the Nordschleife onto the start-finish, the Hohenrain chicane was installed just prior to this section in 1967. This had the twin benefits of reducing the speeds and altering the racing line to a safer position. In 1969, a new pit area was installed, separated from the track by a guardrail for the first time.

Still the concerns remained and, a boycott of the circuit by the Formula One drivers in 1970 resulted in the German GP switching to Hockenheim. To regain the race, the Nürburgring needed to make significant changes.

In February 1971, the bulldozers moved in and began a series of modernizations. Guardrails were installed and wider grass verges were installed across large parts of the circuit. The jumps at Kesselchen and Brünnchen were removed and many trees were felled to create better sightlines at key points. For the traditionalists, this represented a fundamental dumbing down of the circuit; viewed from the modern perspective, this seems a somewhat exaggerated response; the Nürburgring was still the most challenging circuit in the world and, some might say, remained the most dangerous on the F1 calendar.

Formula One returned in 1971, Jackie Stewart triumphing for Tyrrell. It's something of an irony that the man who campaigned most vociferously against the self-evident dangers at tracks like the Nürburgring in the 1960s should prove so successful here; his victory in the torrential 1968 race among the finest ever seen at the 'Ring.

Further changes came in the winter of 1972/73, when construction work on new bridges at Hatzenbach and Breidscheid began, allowing the course to pass at full width beneath them for the first time. Similar modifications were made to the overpass which took the circuit over the Poststraße. Elsewhere, a new entrance to the Südschleife was created further towards the pits, primarily to accommodate a wider entry to the Südkehre, removing the previous bottleneck and allowing the installation of new guardrails and grass verges.

Despite the modernizations, still the dangers remained, compounded by the difficulty of providing effective marshalling and medical care along the 14-mile length. Niki Lauda's fiery crash in 1976 proved a final straw for F1, thought the emerging needs of the TV audience and other commercial and logistical considerations also played their part.

Once F1 departed it was merely a matter of time before others too arrived at the same conclusion. Formula Two continued on, though not without drama; Manfred Winkelhock comprehensively destroying his March BMW when a broken front wing resulted in a backwards somersault as he crested the jump at Flugplatz in 1980. Remarkably, he walked away unscathed.

Sportscars also continued on, though tragedy struck the 1981 1000kms when Herbert Müller died when he lost control avoiding a spinning car and crashed into the earth bank at Kesselchen. It was clear that major change was needed and a more modern, shorter, and fundamentally safer circuit would have to be constructed to guarantee the future of the venue.

Redeveloping the Nordschleife was considered a non-starter, not least due to its history and the high costs involved, but a new Südschleife seemed a feasible proposition. By this time, the original Südschleife had largely been abandoned for racing, having enjoyed none of the security and infrastructure upgrades of the northern loop.

Planning began in the late 1970s, with a variety of proposed layouts suggested, benefiting from input from computer scientists. By 1982, a design had been settled upon, utilizing the existing start-finish straight but little else. The plans called for an ultra-modern facility with wide run off areas and paddock facilities immediately behind the pit garages. The new circuit would sit inside only a small part of the Südschleife , with the remaining original track returned to public use, either as highways or woodland trails. Happily, the new circuit would continue to connect to the Nordschleife, which would be retained for occasional racing use.

The final race on the old Nordschleife was a round of the Veedol Endurance Cup in October 1982, followed by a final club event on the Betonschliefe. Then, in November, the bulldozers moved in, tearing down the pits and Nordkehre, in order to create a new connecting section from Hohenrain to allow the Nordschliefe to function independently during the 1983 season. A new grandstand overlooked this section and housed rudimentary pit and paddock facilities. Greater run-off areas were also created at corners like Aremberg and Brünnchen and further easing of the bumps and jumps at several corners were made and bushes and hedges lining parts of the circuit were replaced with Armco and grass.

As the year unfolded the new Grand Prix circuit gradually began to emerge as racing continued on the slightly truncated original course. During the 1983 1000km, Stefan Bellof set a competition record on the Nordschleife unmatched to this day, lapping his Porsche 956 in an incredible 6:11.13.

After less than two years construction, the new Grand Prix circuit was inaugurated on 12 May 1984, a then relatively-unknown Ayrton Senna beating a host of Formula One drivers in a special race of lightly-modified Mercedes saloon cars. Those attending the opening found the new circuit unpalatably sterile in relation to its older neighbor, but such comparisons were always likely to be unfavorable. It was safe, provided good viewing facilities for spectators and produced decently good racing; in essence, it fulfilled its brief to the full and provided a template for all circuits that followed.

Two visits from Formula One in 1984 and '85 proved a slightly false dawn, with the German GP returning to Hockenheim in 1986. Nevertheless, the circuit firmly re-established its international credentials, hosting a full calender of two and four-wheeled events. The long distance GT and touring car races continued on the Nordschleife, as did the 24 Hours, incorporating the new Grand Prix loop at its southern end. When not entertaining racing or testing, the Nordschleife continued in use as a tourist road – just as it had from its earliest days – but perhaps because of the relative blandness of the new course, it gained even more popularity among the public.

In 1990, the first modification of the new circuit took place, when a link road just to the south of the Kurzanbindung created the Mullenbachschleife, named after the nearby town. It was used for only testing and smaller club events only, due to the lack of pits and paddock facilities.

1995 brought the return of Formula One, as the popularity of Michael Schumacher convinced authorities of the merits of a second race in Germany. A new, tighter, Veedol chicane was installed ahead of the race, though the original also remained in use for motorcycle racing and during the VLN and 24 Hour races.

Improvements continued in 1998, this timeon the Nordschliefe, with the creation of the Grüne Hölle (Green Hell) visitors complex on the Döttinger-Höhe straight. This included a restaurant and car park and provides access to the Nordschleife on tourist days, via ticket barriers, meaning a complete lap at full speed is not now possible on such occasions. Drivers interested in lap times often time themselves from the first bridge after the barriers to the last gantry before the exit (aka Bridge-to-Gantry or BTG time) but this practice is not encouraged and likely to a reprimand from police in the event of a collision (not to mention likely invalidation of insurance). You have been warned!

New pits sprang up in 2000, with better facilities, especially for the 24 Hour race which regularly attracted 200+ entries. Then, in 2002, the most significant changes were made since the creation of the GP circuit, with the addition of the Mercedes Arena, almost inevitably designed by Hermann Tilke. The following year, the F1 chicane was revised, to a Z-shaped configuration suggested by Michael Schumacher and paid for thanks to the German star donating his time for free at a special spectator day. It was not a popular change among his F1 compatriots.

While no further changes have been made to the track, 2009 saw the completion of a controversial scheme to incorporate a leisure park and shopping center into the facilities behind the main grandstand. Completed under the promise of private investment, the regional government through a state-owned bank stepped in to save the project with €350 million of public funds when the original investors ran out of funds.

Visitor numbers at thecomplex have been far below those projected, with the huge complex often resembling a ghost town. A high-speed roller coaster stands forlornly as a symbol of all that has gone wrong at the circuit, having never taken a paying passenger after health and safety concerns following two crashes in testing forced its closure soon after completion.

Instead of pulling the plug, the regional government rented the park – including both race tracks – back to the same privateers who were driving forces behind the leisure park's initial private setup, Kai Richter and Jörg Lindner. The pair continued to run the park – dubbed Nüro-Disney by locals – with increasingly odd non-motorsport events to try and pull in the punters. Inevitably, visitors were more interested in motorsport and the track beyond then high-end boutiques and, in February 2012, the contract was cancelled and the government took control.

By the end of 2012, the government declared the circuit bankruptcy and the administrators put up the for sale signs in 2013. Three bidders were in the running but in March 2014 the circuit was finally sold to the German-based Capricorn Group for 100 million Euros, although the formal change in ownership will not be complete until January 2015. The purchase price includes the boulevard, hotels, Grand Prix track, the physical land and the Nordschleife. Düsseldorf-based automotive supplier Capricorn already have a presence within the facility, where it makes a variety of engine components and has more than 350 employees, 100 of whom work at a factory at the Nürburgring.

Capricorn have pledged to invest 25 million Euros once it assumes ownership, announcing it will continue to host racing, tourist days and operation of the hotel. Part of the plans include the development of an ‘Automotive Technology Cluster’ for engineering and other automotive businesses and educational establishments. Capricorn plans to close the rollercoaster and the inconvenient ‘Ring Card’ payment system, and demolish the Grüne Hölle (Green Hell) restaurant complex to make room for the Automotive Technology Cluster.

In the meantime, the administrators continue to operate the circuit as a going concern. For those interested in the future of the circuit, the 'Save the Ring' campaign group is still active in campaigning to safeguard the Nürburgring's future – see their website for more details and show your support by the displaying the STR logo.

A sad footnote is the tragic death of a spectator at the Flugplatz section of the Nordschliefe during the first VLN race of the 2015 season. For reasons which are still being investigated, the Nissan GTR GT3 of Jann Mardenborough became airborne as it crested the hill and somersaulted into a spectator area. One spectator was succumbed to their injuries a short time later and a number of others were injured.

In the immediate aftermath, the DMSB (Germany's motorsport governing body) suspended the racing licence of the Nordschliefe for the top SP7, SP8, SP9, SP10 and SP-X classes. A full investigation will follow, which will look at what changes may be necessary in order to allow the classes to operate again on the circuit.

Above all other circuits, the Nürburgring has a history and tradition which is intertwined with that of the motorsport itself. The 'Green Hell', as Jackie Stewart so memorably described it, has been thrilling and terrifying drivers in equal measure since 1927 and any event here remains one of the greatest spectacles and challenges on the sporting calendar.

Like many of the lavish venues established in the modern era by oil-rich states seeking to boost their country's international status, the Nürburgring owes its existence to political manoeuvrings. When in 1907, Felice Nazzaro won the Kasierpreis for the Italian Fiat outfit at Taunus, near Frankfurt, German pride took a severe dent. When the Kaiser demanded an explanation for the unexpected result, he was told that the defeat was due to the German manufacturers having no suitable home track to develop and race their vehicles.

Imperial consent was soon given to create such a facility and plans began to be formulated for a world-beating track in the region surrounding the town of Adenau near the Eifel Mountains. But just as the project gathered steam in earnest, World War I intervened and trivial pursuits such as racing took a back seat.

Emerging defeated from the war, Germany was a broken nation, with a valueless currency, mass unemployment and hardship in almost every family. Yet it was just this backdrop which saw the plans for the circuit revived. While tentative moves in 1920 foundered due to a lack of funds, supporters of the project persevered, convinced it could offer a competitive advantage for the resurgent German motor industry.

One man in particular stands as the father of the Nürburgring; Dr Otto Creutz was chair of the ADAC (Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobile Club) and a passionate believer in the project. He reached agreement with the Mayor of Cologne (and future Chancellor) Konrad Adenauer for the project to go ahead as a means of relieving the chronic unemployment in the region.

The first stone was laid on September 27, 1925, and for the next two years around 2,500 workmen laboured to construct the circuit. The basic layout was set by Hans Weidenbrück, using the rolling hillsides and plateaus around the Schloß Nürburg to create a massive circuit that was a true test of both man and machine. Designed to be completely separate from the public road network, it nevertheless incorporated a certain amount of normal road character, increasing its relevance for automobile testing. In part, existing roads and trails were followed, particularly in the area from Hatzenbach to Adenauer Forst and much of the Südschleife, while other sections were totally new, particulalry from Breidscheid to Hedwigshöhe.

There were two main circuits, a northern loop (Nordschleife in the local language) of 14.18 miles and a shorter southern circuit, the Südschleife at 4.81 miles long. Where the two intersected at the shared start/finish straight, a short link circuit could also be used, popularly known as the Betonschleife ('Concrete Loop') though officially titled Start-und-Ziel-Schleife. Both north and south loops could be combined to form 17.58 mile leviathon, though this was rarely used for racing beyond the 1931 season. In addition, a steep test track, the Steilstrecke, was also constructed to make use of the steep climb between Klostertal and Hohe Acht and featuring gradients of up to 27%.

The new circuit was constructed in four sections, each by a different contractor, with the Nordschleife completed first in 1926, the Südschleife and Steilstrecke courses being completed the following year. Innovations at the new course included a large garaged paddock area, connected to the pits via a tunnel, a 10,000 seat grandstand (another quickly followed), a hotel, restaurant and control tower. A series of telephone connections allowed for communication around the giant northern loop by post-to-post calls at 10 (later 16) marshal huts.

Total costs for construction ran to 15 million marks, including 6 million marks provided by the government and substantial finance from the city of Cologne. A competition was held to name the new circuit, with the winning entry suggested by a retired government official from Bad Godesberg.

The Nordschleife opened for racing action in June 1927, with the first race actually for motorbikes on June 18 and won by Tony Ulmen on a Velocette. The following day Rudolph Caracciola entered the record books as the first four wheeled winner, triumphing in a supercharged Mercedes S. The Grand Prix arrived on July 17, won in another Mercedes S by Otto Merz. Thereafter the 'Ring established itself as one of the toughest Grands Prix on the racing calendar.

One of the Nordschleife's defining characteristics found itself literally set in stone (well, concrete) during the 1933 season. At the Karrousel, Rudolf Carraciola had been in the practice of hooking his inside wheel into the ditch to guide the car round – gaining himself as much as two seconds per lap in the process. After several years where other competitors began to copy this innovation, the ditch was finally concreted over and the banked corner was born. Over time, the banked section was extended further, allowing the whole car to be positioned on the concrete section allowing for a slingshot around the hairpin.

World War II provided an inevitable interruption to activities. The Sporthotel grandstand was set up to accommodate evacuees from bombed cities and later served as a military hospital. Other parts fo the circuit were turned into arable and pasture land – cattle even being kept in the lower rooms of the Mercedes tower. In the last months of the war the track was badly damaged by the tanks of the advancing Allies and the grandstand hotel and administrative buildings were destroyed.

When peace returned, the process of rebuilding and reopening the circuit began. The Südschleife reopened first, hosting a motorcycle Eifel Cup race in August 1947. To attract the crowds, race organizers took the novel approach of offering every ticket holder a meal of two sausages, potato salad, bread and half a liter of wine. Unsurprisingly, it worked and people flocked to the meeting.

A year later and the repair works began on the Nordschleife, with racing resuming in May 1949. Soon racing categories of all kinds returned, from sportscars to single seaters. Formula Two came first in 1950, followed by Formula One in 1951. The Nürburgring was back as an international venue of note.

The Dunlop scoring tower was erected in 1954, the first electronic scoring board of its type in the world. Various resurfacings took place in the following years; the start/finish in 1957, Schwedenkreutz to Pflantzgarten in 1965. Still the circuit retained its narrow hedge and tree-lined corners and safety concerns grew. Over the years, several drivers lost their lives; Čeněk Junek is generally regarded as the first in 1928, but Onofre Marimón, Peter Collins, Count Carel Godin de Beaufort and Gerhard Mitter also all perished while racing on the Nordschliefe.

By the end of the 1960s, the first significant changes began to be made in response to these mounting safety concerns. After several near-misses with the Dunlop scoring tower as cars drifted through the high-speed curve that lead from the Nordschleife onto the start-finish, the Hohenrain chicane was installed just prior to this section in 1967. This had the twin benefits of reducing the speeds and altering the racing line to a safer position. In 1969, a new pit area was installed, separated from the track by a guardrail for the first time.

Still the concerns remained and, a boycott of the circuit by the Formula One drivers in 1970 resulted in the German GP switching to Hockenheim. To regain the race, the Nürburgring needed to make significant changes.

In February 1971, the bulldozers moved in and began a series of modernizations. Guardrails were installed and wider grass verges were installed across large parts of the circuit. The jumps at Kesselchen and Brünnchen were removed and many trees were felled to create better sightlines at key points. For the traditionalists, this represented a fundamental dumbing down of the circuit; viewed from the modern perspective, this seems a somewhat exaggerated response; the Nürburgring was still the most challenging circuit in the world and, some might say, remained the most dangerous on the F1 calendar.

Formula One returned in 1971, Jackie Stewart triumphing for Tyrrell. It's something of an irony that the man who campaigned most vociferously against the self-evident dangers at tracks like the Nürburgring in the 1960s should prove so successful here; his victory in the torrential 1968 race among the finest ever seen at the 'Ring.

Further changes came in the winter of 1972/73, when construction work on new bridges at Hatzenbach and Breidscheid began, allowing the course to pass at full width beneath them for the first time. Similar modifications were made to the overpass which took the circuit over the Poststraße. Elsewhere, a new entrance to the Südschleife was created further towards the pits, primarily to accommodate a wider entry to the Südkehre, removing the previous bottleneck and allowing the installation of new guardrails and grass verges.

Despite the modernizations, still the dangers remained, compounded by the difficulty of providing effective marshalling and medical care along the 14-mile length. Niki Lauda's fiery crash in 1976 proved a final straw for F1, thought the emerging needs of the TV audience and other commercial and logistical considerations also played their part.

Once F1 departed it was merely a matter of time before others too arrived at the same conclusion. Formula Two continued on, though not without drama; Manfred Winkelhock comprehensively destroying his March BMW when a broken front wing resulted in a backwards somersault as he crested the jump at Flugplatz in 1980. Remarkably, he walked away unscathed.

Sportscars also continued on, though tragedy struck the 1981 1000kms when Herbert Müller died when he lost control avoiding a spinning car and crashed into the earth bank at Kesselchen. It was clear that major change was needed and a more modern, shorter, and fundamentally safer circuit would have to be constructed to guarantee the future of the venue.

Redeveloping the Nordschleife was considered a non-starter, not least due to its history and the high costs involved, but a new Südschleife seemed a feasible proposition. By this time, the original Südschleife had largely been abandoned for racing, having enjoyed none of the security and infrastructure upgrades of the northern loop.

Planning began in the late 1970s, with a variety of proposed layouts suggested, benefiting from input from computer scientists. By 1982, a design had been settled upon, utilizing the existing start-finish straight but little else. The plans called for an ultra-modern facility with wide run off areas and paddock facilities immediately behind the pit garages. The new circuit would sit inside only a small part of the Südschleife , with the remaining original track returned to public use, either as highways or woodland trails. Happily, the new circuit would continue to connect to the Nordschleife, which would be retained for occasional racing use.

The final race on the old Nordschleife was a round of the Veedol Endurance Cup in October 1982, followed by a final club event on the Betonschliefe. Then, in November, the bulldozers moved in, tearing down the pits and Nordkehre, in order to create a new connecting section from Hohenrain to allow the Nordschliefe to function independently during the 1983 season. A new grandstand overlooked this section and housed rudimentary pit and paddock facilities. Greater run-off areas were also created at corners like Aremberg and Brünnchen and further easing of the bumps and jumps at several corners were made and bushes and hedges lining parts of the circuit were replaced with Armco and grass.

As the year unfolded the new Grand Prix circuit gradually began to emerge as racing continued on the slightly truncated original course. During the 1983 1000km, Stefan Bellof set a competition record on the Nordschleife unmatched to this day, lapping his Porsche 956 in an incredible 6:11.13.

After less than two years construction, the new Grand Prix circuit was inaugurated on 12 May 1984, a then relatively-unknown Ayrton Senna beating a host of Formula One drivers in a special race of lightly-modified Mercedes saloon cars. Those attending the opening found the new circuit unpalatably sterile in relation to its older neighbor, but such comparisons were always likely to be unfavorable. It was safe, provided good viewing facilities for spectators and produced decently good racing; in essence, it fulfilled its brief to the full and provided a template for all circuits that followed.

Two visits from Formula One in 1984 and '85 proved a slightly false dawn, with the German GP returning to Hockenheim in 1986. Nevertheless, the circuit firmly re-established its international credentials, hosting a full calender of two and four-wheeled events. The long distance GT and touring car races continued on the Nordschleife, as did the 24 Hours, incorporating the new Grand Prix loop at its southern end. When not entertaining racing or testing, the Nordschleife continued in use as a tourist road – just as it had from its earliest days – but perhaps because of the relative blandness of the new course, it gained even more popularity among the public.

In 1990, the first modification of the new circuit took place, when a link road just to the south of the Kurzanbindung created the Mullenbachschleife, named after the nearby town. It was used for only testing and smaller club events only, due to the lack of pits and paddock facilities.

1995 brought the return of Formula One, as the popularity of Michael Schumacher convinced authorities of the merits of a second race in Germany. A new, tighter, Veedol chicane was installed ahead of the race, though the original also remained in use for motorcycle racing and during the VLN and 24 Hour races.

Improvements continued in 1998, this timeon the Nordschliefe, with the creation of the Grüne Hölle (Green Hell) visitors complex on the Döttinger-Höhe straight. This included a restaurant and car park and provides access to the Nordschleife on tourist days, via ticket barriers, meaning a complete lap at full speed is not now possible on such occasions. Drivers interested in lap times often time themselves from the first bridge after the barriers to the last gantry before the exit (aka Bridge-to-Gantry or BTG time) but this practice is not encouraged and likely to a reprimand from police in the event of a collision (not to mention likely invalidation of insurance). You have been warned!

New pits sprang up in 2000, with better facilities, especially for the 24 Hour race which regularly attracted 200+ entries. Then, in 2002, the most significant changes were made since the creation of the GP circuit, with the addition of the Mercedes Arena, almost inevitably designed by Hermann Tilke. The following year, the F1 chicane was revised, to a Z-shaped configuration suggested by Michael Schumacher and paid for thanks to the German star donating his time for free at a special spectator day. It was not a popular change among his F1 compatriots.

While no further changes have been made to the track, 2009 saw the completion of a controversial scheme to incorporate a leisure park and shopping center into the facilities behind the main grandstand. Completed under the promise of private investment, the regional government through a state-owned bank stepped in to save the project with €350 million of public funds when the original investors ran out of funds.

Visitor numbers at thecomplex have been far below those projected, with the huge complex often resembling a ghost town. A high-speed roller coaster stands forlornly as a symbol of all that has gone wrong at the circuit, having never taken a paying passenger after health and safety concerns following two crashes in testing forced its closure soon after completion.

Instead of pulling the plug, the regional government rented the park – including both race tracks – back to the same privateers who were driving forces behind the leisure park's initial private setup, Kai Richter and Jörg Lindner. The pair continued to run the park – dubbed Nüro-Disney by locals – with increasingly odd non-motorsport events to try and pull in the punters. Inevitably, visitors were more interested in motorsport and the track beyond then high-end boutiques and, in February 2012, the contract was cancelled and the government took control.

By the end of 2012, the government declared the circuit bankruptcy and the administrators put up the for sale signs in 2013. Three bidders were in the running but in March 2014 the circuit was finally sold to the German-based Capricorn Group for 100 million Euros, although the formal change in ownership will not be complete until January 2015. The purchase price includes the boulevard, hotels, Grand Prix track, the physical land and the Nordschleife. Düsseldorf-based automotive supplier Capricorn already have a presence within the facility, where it makes a variety of engine components and has more than 350 employees, 100 of whom work at a factory at the Nürburgring.

Capricorn have pledged to invest 25 million Euros once it assumes ownership, announcing it will continue to host racing, tourist days and operation of the hotel. Part of the plans include the development of an ‘Automotive Technology Cluster’ for engineering and other automotive businesses and educational establishments. Capricorn plans to close the rollercoaster and the inconvenient ‘Ring Card’ payment system, and demolish the Grüne Hölle (Green Hell) restaurant complex to make room for the Automotive Technology Cluster.

In the meantime, the administrators continue to operate the circuit as a going concern. For those interested in the future of the circuit, the 'Save the Ring' campaign group is still active in campaigning to safeguard the Nürburgring's future – see their website for more details and show your support by the displaying the STR logo.

A sad footnote is the tragic death of a spectator at the Flugplatz section of the Nordschliefe during the first VLN race of the 2015 season. For reasons which are still being investigated, the Nissan GTR GT3 of Jann Mardenborough became airborne as it crested the hill and somersaulted into a spectator area. One spectator was succumbed to their injuries a short time later and a number of others were injured.

In the immediate aftermath, the DMSB (Germany's motorsport governing body) suspended the racing licence of the Nordschliefe for the top SP7, SP8, SP9, SP10 and SP-X classes. A full investigation will follow, which will look at what changes may be necessary in order to allow the classes to operate again on the circuit.