The standard corner rules

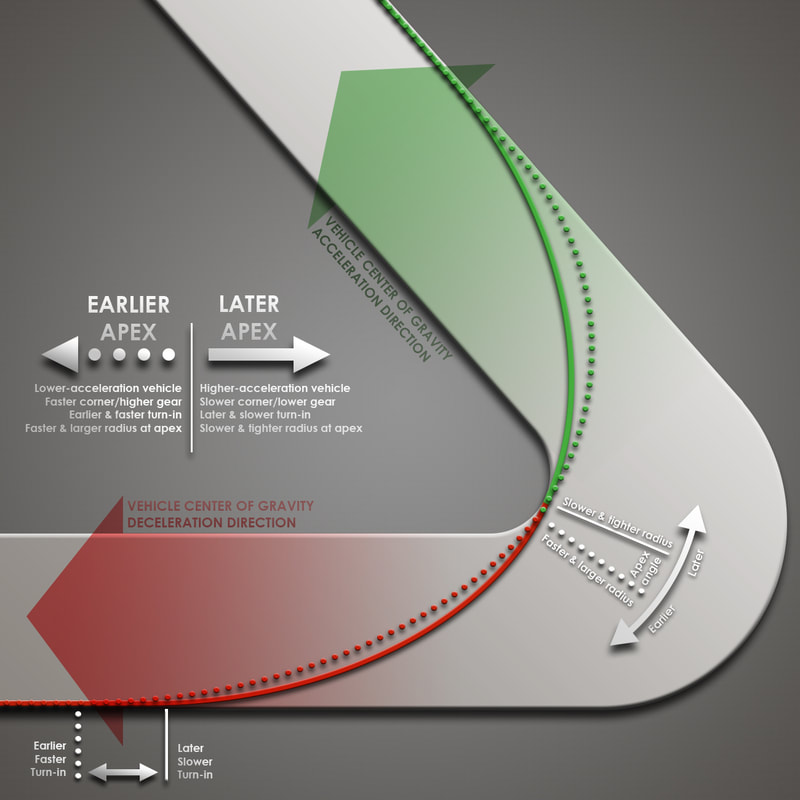

- The ideal apex is determined by a car’s lateral vs longitudinal acceleration capabilities for a given corner. As a car’s ability to accelerate in relation to its cornering ability increases, it will need a later, slower apex. The illustration shows two lines. The solid line represents a 4-wheel drive car with enough power to keep all four tires at the limit throughout the entire corner exit. It has an Euler spiral shaped exit line. The dotted line represents a car that cannot accelerate even at full throttle. It has a circular exit line. Almost every vehicle will have an exit line between these two extremes.

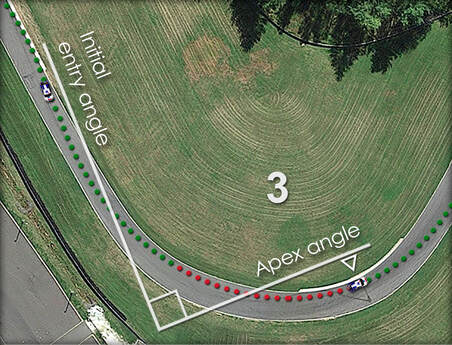

- The apex should be the most limiting point along the inside of the track and also the point of minimum speed attained in the corner. With few exceptions, such as rear-brake karts that need a somewhat more circular entry, nearly every vehicle should have a corner entry path up to this apex in the shape of an Euler Spiral. The later apex in the illustration has a smaller spiral and goes along this spiral further, but they are both the same shape. I primarily look for a steady reduction in speed as the main indicator of a correct spiral shaped entry.

- The braking point does not affect this ideal corner entry path. Depending on the needed deceleration point, a driver may begin with straight-line braking prior to entering the spiral or they may continue into the spiral at full-throttle before switching to deceleration. If a driver enters the spiral at full-throttle however, they shouldn’t reach the limit until they begin decelerating.

- A car should either achieve full throttle at the apex or, if this is impossible due to wheelspin, not until the car is going nearly straight at the end of the corner. In the event of wheelspin, progressive power should be applied throughout corner exit. Progressive power doesn’t necessarily mean progressive throttle however, it depends on the shape of the car’s power band.

- While being as close to neutrally balanced as possible, a car should be at the understeer limit during corner entry, and the oversteer limit during corner exit. While these are the ideal states, they are not always possible unless a car’s setup is optimized for a certain corner. A full throttle exit, for example, will often be at the understeer limit, but a driver shouldn’t consider this an error and try to induce oversteer to correct.

- A standard corner racing line should typically take up the entire width of the track, and a driver can use this to determine their ideal apex. There are rare exceptions, which we’ll cover in a later rule, but if a driver doesn’t need the entire width of the track, they should use an earlier, faster apex. Likewise, if the driver runs wide at corner exit, this doesn’t mean they need to apply less throttle, it means they need a later, slower apex.

The chicane rule

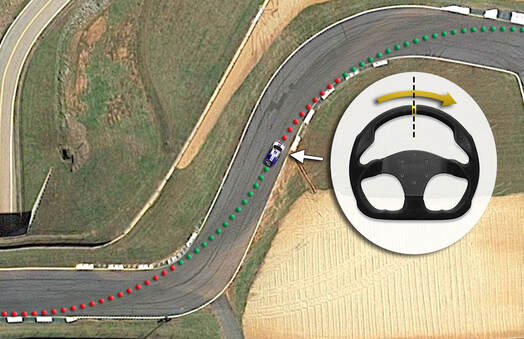

- The ideal chicane transition point requires immediate deceleration as the steering passes over center toward the 2nd apex. This links the two apexes, so if a driver needs a later 2nd apex to optimize the final corner exit, they should drive a later 1st apex… and vice versa.

The ideal chicane transition point requires immediate deceleration as the steering passes over center.

The ideal chicane transition point requires immediate deceleration as the steering passes over center. The Double Apex Rule

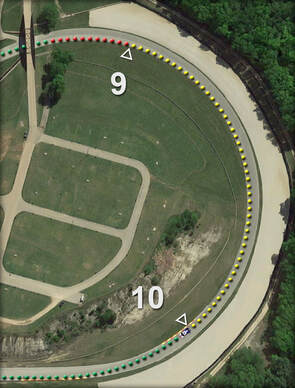

- To optimize a double apex, a driver should avoid a speed reversal between the two apexes. This links the two apexes, so if a driver needs a later 2nd apex to optimize the corner exit, they should drive an earlier 1st apex… and vice versa. A speed reversal would be accelerating and then decelerating or accelerating and then decelerating. There should be a steady change in speed between the two apexes.

You would want to avoid this speed reversal by simply hugging the inside and driving as fast as possible at a constant speed. In fact, simply driving a constant speed is what a double apex corner would require if the entry and exit were even. Just as in a chicane however, we have increasing radius double apexes where the driver would steadily increase speed between the two apexes, and decreasing radius double apexes where the driver would steadily decrease speed. The key here is that once a driver begins decelerating or accelerating as they pass the 1st apex, they should maintain this until they reach the 2nd apex and their corner exit begins.

The Full Throttle Corner Rule

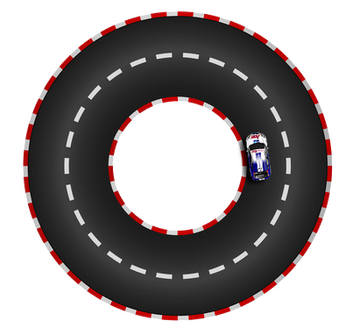

- To optimize a full-throttle corner, a driver should drive the shortest path possible by setting their entry spiral to ensure the car reaches the limit just as they pass the apex. The driver should then continue at the limit, turning the vehicle until it is aimed directly at the next corner.

A four corner continuum

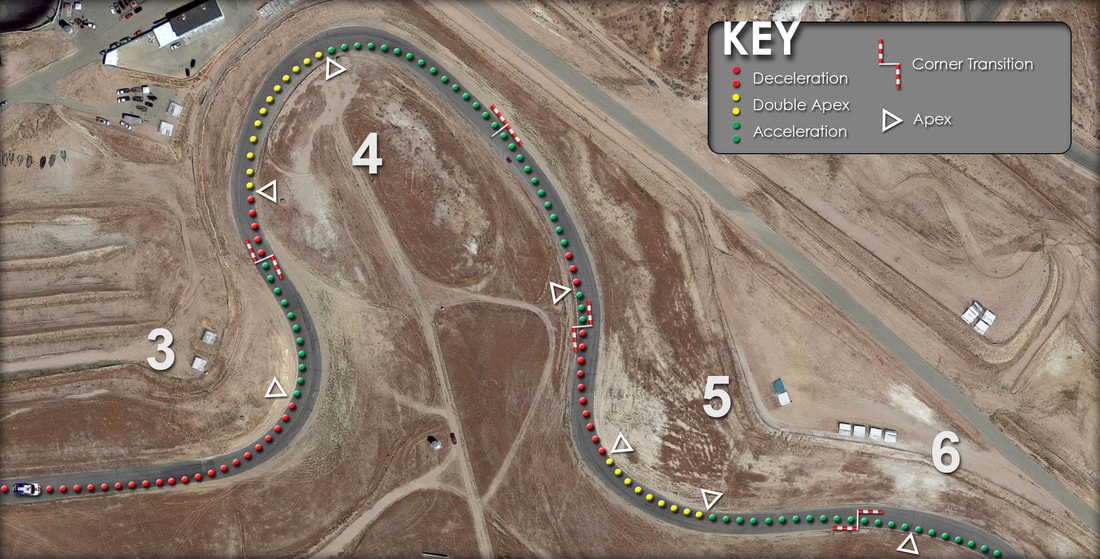

Turns 3 through 6 at Willow Springs is a complex sequence containing all four corner types.

Turns 3 through 6 at Willow Springs is a complex sequence containing all four corner types. Understanding how the rules fit together and how one type of corner blends into the next is important, because often the most difficult parts of a track are the one ones right on the edge between one corner type and another. I do have one more rule I want to go over however, and although it’s not a new corner type, it’s important enough that I wanted to discuss it separately. The 90-Degree Limit Rule.

The 90-degree Limit Rule

- Neither a driver’s entry nor exit arc should exceed 90 degrees.

Click the image for a more detailed break down of Lime Rock Park.

Click the image for a more detailed break down of Lime Rock Park. You always want to use up to 90 degrees for your entry or exit if possible, but no more. For newer drivers, I often have them use aerial shots to find reference markers helping them stay within the 90-degree limit. As drivers advance in skill however, they often no longer need these reference markers as they learn to start driving based on the core principles of line theory itself.

No more Rules

The best drivers I have ever worked with always have the uncanny ability to predict their times. This is no coincidence because an elite level driver has learned “what fast feels like” and that’s why they can do it at any track, with any car. It’s this ability that allows a driver to move past the rules and begin to simply follow the core principles of line theory itself by actually learning to feel how well they are generating forces in the ideal directions. I call this the “Universal Cue” and I named it this because eventually it is all that is needed. You can watch a world class driver’s lap and see them correctly following all the rules, but none of this was pre-planned or intentional, they just followed the core principle of line theory and that was the result.

by Adam Brouillard