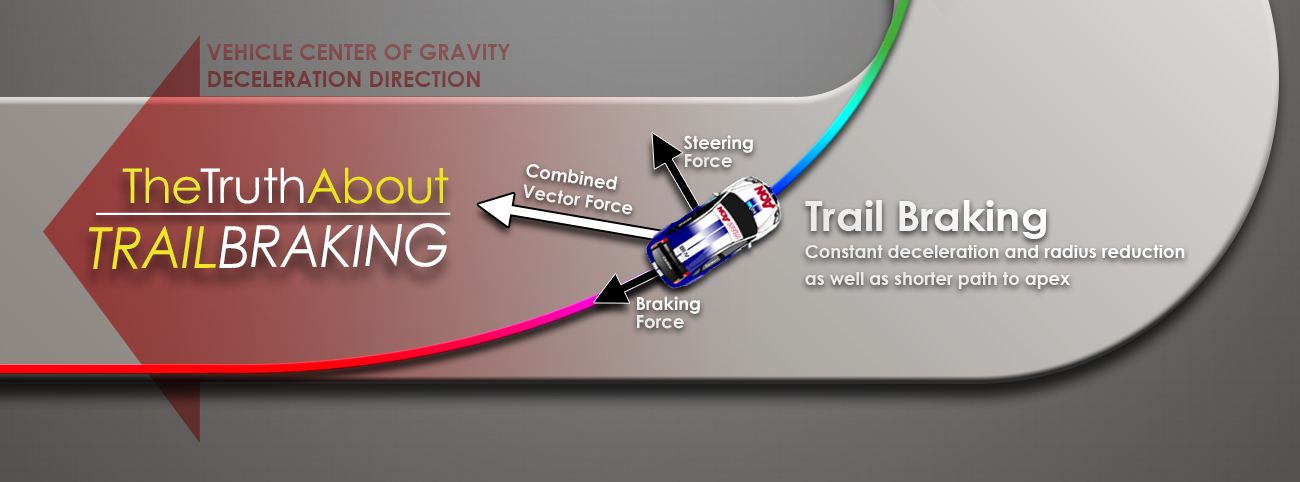

In basic terms, trail braking happens any time you decelerate a vehicle past the point of turn-in. Interestingly, the only reason we even have the term is that traditionally many drivers thought straight line only braking was the way to go. Continuing to brake into a turn was considered a special technique that may, or may not, be faster. We’ve come a long way since then however, and although some may still argue over the specifics of when and how trail braking should be done, it’s generally understood that learning it is required if you wish to have competitive times.

I really don’t like the term "trail braking” very much however. I think it can lead to confusion because although you should ideally decelerate all the way to the apex during corner entry, this doesn’t necessarily mean you should use the brakes the entire way. Induced drag on the tires from slip angle as well as engine braking and aerodynamic drag are all already acting on the vehicle to slow it down. Depending on the car and corner, you won’t always need to continue using brakes in the final part of corner entry to achieve the proper deceleration rate. In fact, aerodynamic drag can be so powerful in fast corners sometimes that you might even need to use moderate throttle so that you don’t decelerate too quickly!

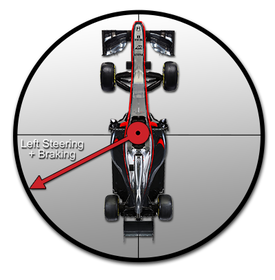

Traction circle showing combined braking and turning at the limit.

Traction circle showing combined braking and turning at the limit. Putting these two principles together, consider a high-speed corner where only a brief throttle lift was needed. The shape of the ideal entry line would again remain the same, but the deceleration forces to drop that small amount of speed near the apex all came from drag forces when you lifted the throttle. Even though you never touched the brakes, you are still following the same principles that make “trail braking” the ideal corner entry technique.

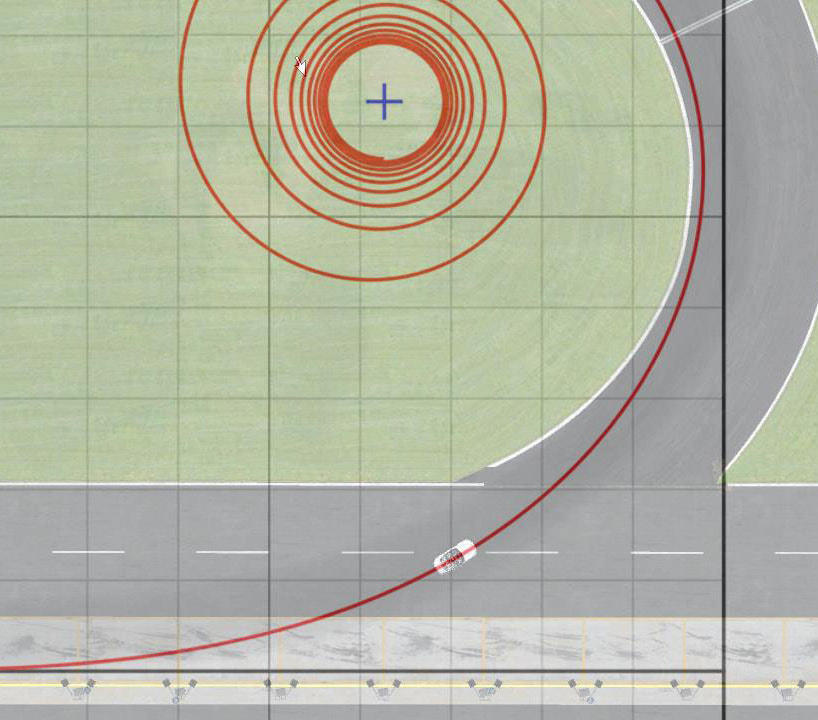

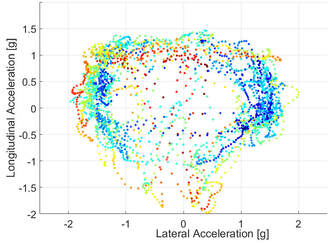

G-G Diagram

G-G Diagram So now that we’ve looked at what trail braking is, let’s look at a few things that it’s not. You often hear that you can tell how good at trail braking someone is by looking at how rounded their traction circle (G-G diagram) readout is as they transition from braking to turning. While being able to keep a vehicle at the edge of the traction circle does indicate good car control abilities, it doesn’t necessarily indicate a good corner entry. I’ve worked with many drivers who had a great looking traction circle readout, but were losing time during entry and were not able to figure out why. For some examples of how this can happen, check out the linked video. In the video, I demonstrate three different types of lines through a corner. Although I always kept the car at the very edge of the traction circle as I transition from brakes to turning, the times produced were very different. While learning to keep the car at the edge of the traction circle is an essential skill, to find that last bit of time, you also have to learn to be at the right place on the circle, at the right time.

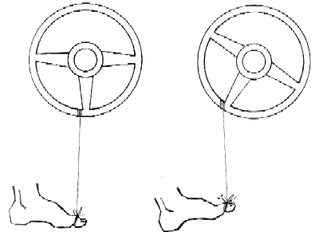

When first learning to trail brake, I recommend starting with a straightforward approach to initially just get used to the basic idea. During corner entry, just try to focus on steadily increasing steering while also steadily releasing the brakes. An old visualization trick to help with this is to imagine one end of a string tied to the bottom of the steering wheel and the other tied to your toe. As you turn the steering wheel more, the string would begin to pull your foot off the brake.

It’s a good idea to spend some time to make sure you can accomplish this part, because once you pick up the pace, the difficulty can ramp up quickly. Depending on the vehicle and corner, the car control challenge alone of driving at the limit during trail braking ranges from hard to seemingly impossible. As I mentioned earlier though, even once you do learn to ride the edge of the traction circle, there are still plenty of ways to lose time while trail braking. That is because the goals of corner entry are a bit of a paradox. While an ideal corner entry maximizes deceleration, if you actually concentrate on doing this, you could very well over-slow the corner without even realizing it.

One of the very first visualization exercises I like to go through with a driver helps to explain the corner entry paradox. Imagine you are in a braking challenge where you cross a start line at any speed you wish and then try to stop with the front tires in a small strip 50 meters away as quickly as possible. If the tires go past the strip, you lose. Following line theory principles, we can understand that the ideal result would come from crossing the start line at the exact speed that would allow us to threshold brake for the entire 50 meters landing the front tires right on the strip.

This shifting of focus to how your vehicle is actually moving around the track is also an important step in a driver’s journey. In the beginning, as you are learning the basic mechanics, visualization techniques such as the string, which primarily focuses on memorized control patterns, can be helpful. Eventually however, you will need to move beyond this if you wish to continue progressing. I have seen countless drivers who hit a skill plateau, as they try to essentially memorize an ever more complex sequence of control inputs around a race track, in an attempt to find lap time. Not only is this approach quite limiting, speaking from experience, it’s also not very fun.

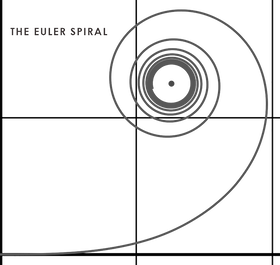

What is not only a lot more fun, but also quite amazing to see for most drivers, is when someone can jump into an unfamiliar car at a new track and quickly start laying down competitive laps. Their data might show picture perfect Euler spiral entries with ideal steering and brake traces, but none of this was planned or memorized. Instead, through proper training, they have learned to focus on the true goals as they drive, and that was simply the result.

I hope you enjoyed this lesson and if you have any questions, please use the comments section below. Up next, we’ll look take a deeper look at the physics of trail braking. If you are interested in a complete guide to the physics of racing, we also offer The Science of Speed book series, available through our bookstore or at popular retailers such as Amazon.